04 Apr “Don’t Round Your Spine!” they say…

When we have low bone density, we hear all the time “don’t round your spine!”

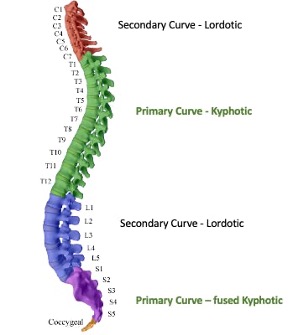

But while this message has good intent, somewhere along the line many people seem to have lost the understanding that a neutral spine is a multi-curved spine! And they might think that the person in the image above is dangerously ’rounding’ her spine.

The message I want you to take away for your yoga practice is that we need to embrace the buoyant curves of our spine and learn to better understand their purpose and capacity – and how to move our own spine wisely with the support of our whole body and breath.

Let’s explore this a bit further.

We relate to the world through our spine.

Consider this perspective on the various sections of the design of our spine:

The cervical spine – aka the neck – resides above the torso facilitating the mobility of the head to tune into our senses – seeing, hearing, smelling, and tasting the world around us.

The thoracic spine – aka the upper back – is connected to the rib cage that embraces the heart and lungs and sprouts our arms and hands with which we interact with the world.

The lumbar spine – aka the low back – is the weight-bearing workhorse and support of the space for digesting our world.

The sacrum + coccyx nestles into and becomes indistinguishable from the pelvis interlocked with our legs and feet with which we ambulate through the world.

Our spine is truly amazing.

It’s designed to move in many different directions (flexion, lateral flexion, extension, axial extension, rotation, and combinations of these.)

Each section of our spine has a set range of motion (in each of those directions) and, yet, of course, the capabilities of our personal spine varies within these ranges.

The “rounding” is usually referring to the flexion of the upper spine.

In yoga poses, some people call it forward folding, some people call it forward bending.

I prefer the alliteration of ‘forward fold’ but I can see how to some people ‘bending’ is more descriptive of the general shapes we’re referring to. Especially as depicted by stick figures. Here are a couple of examples:

Yet, this is where the confusion lies around understanding the true nature of the “rounding” of the torso.

Again, we have to understand that a “neutral” spine is a multi-curved spine and that “flexion” is naturally increasing the kyphotic curve of the upper back and simultaneously decreasing the lordotic curves of the low back and neck. Dispersing the stretch through the whole spine – not concentrating the effort in one area.

And guess what?

These yoga pose shapes (as depicted by the stick figures) are not attained just from spinal flexion (in fact relying just on our spine to get us into and out of these shapes is problematic.) The hips, the shoulders, the legs, the feet are all involved – and even, more importantly, the breath!

What are we bending or folding? And what is the function? Again I’m talking specifically about yoga poses.

We’re moving the top half over the lower half – to stretch the whole backside of the body.

The connection along the backside of the body runs from the soles of your feet up to your skull. Tom Myers in Anatomy Trains calls this the Superficial Back Line.

The full stretch of the forward bending/folding shape involves a lot of tissues and joints.

And the getting into and out of the shapes is where we notice what tissues and joints we’re actually able to recruit for the experience.

Go slow. Check it out.

In my Yoga for Our Vital Bones classes, you learn to use the breath to support the spine, always, and especially in these shapes.

You practice how to exhale to support the low spine by bowing over the belly to get into the shape, and then practice how to inhale to extend through the ribs and chest cavity to get out of the shape. This is a technique taught in the Viniyoga lineage.

The breath supports the spine so we can use ALL the joints of the spine as well as all the joints that connect to the whole backline of the body – including the feet!

Hinging at the hips will bypass a lot of joints, putting them at a disadvantage from disuse, and could inadvertently cause adverse effects by overusing other joints (e.g., hips? knees?) rather than dispersing the stretch over the whole body. (1)

~~~

I know it isn’t very popular to say that flexing your spine is not inherently dangerous for the vast majority of us with low bone density – and most especially if you are doing it slowly with breath support in a sensible yoga class.

Unfortunately, the party-line follows what was at the time (1984) considered a “landmark” study on the effects of flexion vs extension of the spine on people with osteoporosis. If you look at the results of the study, it was clear that the groups that did flexion exercises or flexion and extension exercises experienced more vertebral compression fractures than the groups that did only extension or no exercise at all. BUT you need to know that the two flexion exercises that were done were a simple seated spinal stretch and old fashioned abdominal crunches (i.e., rapid, successive, limited range of motion of the spine and adjoining joints – the compression fractures that resulted were predominantly in the T6-T8 vertebrae.) Since there were two flexion exercises, it’s not clear if one or both were at fault but my money is on the crunches as the culprit to the fractures. (2)

We know so much more now than we did 40 years ago so why are we still repeating this statement about flexion?

And how does this study relate to what we do in yoga? When it comes to yoga, students always want to know what poses they should do for the benefits or avoid for the sake of safety. Many lists of poses to avoid include what they call ’rounding’ poses. But I hope what I have explained so far makes you question this nomenclature. And let’s be clear that yoga and bone health are not a one-size-fits-all situation, so a simple list does not suffice.

The condition of low bone density can manifest in our 40s or 50s, and we could live another 5 decades more. Each individual and each decade of life has its own capacities to take into consideration, so we must address poses on a case-by-case basis. Consider your fitness level, experience with yoga, sense of body awareness, history of injuries, and myriad other conditions—not just the number from your DXA scan.

Yes, there are certainly exercise movements and specific yoga poses that some people with low bone density should avoid or modify greatly (halasana <plow pose> comes to mind) but to say that ALL people with low bone density should avoid ALL flexion based on this old study using abdominal crunches is too broad of a statement generating a wave of fear and anxiety, and likely triggering a nocebo response where a negative outcome occurs due to a belief that a negative outcome will occur.

Let’s broaden our understanding of how the body works, how the spine works with the rest of your body, and what forces are truly at play that may put you at risk of vertebral fractures.

Note that the BoneFit(tm) Movement Guidelines have been revised to limit flexion movements of the spine that are “repeated, sustained, weighted, end-range, rapid, and forceful” – not avoid altogether. Yes!

There is generally a wide gap between end-range and zero range in which we can move mindfully.

Going forward, I’m hoping we can all approach this messaging about flexion and “rounding” more sensibly.

Each person is an individual, with individual capabilities that need to be evaluated. I invite yoga teachers to become more educated on bone-informed yoga practices for people who have low bone density and specifically how to use the breath to support what’s appropriate for your students, without just blindly adopting PT movement techniques that do not even mention breath support. We teach yoga, which employs the breath for many reasons, not the least of which is for spinal support.

The vast majority of yoga poses that involve flexion of the spine are perfectly safe for most people with low bone density if done slowly to your capacity and with the breath.

Not sure if you are doing them this way? Please contact me for a free evaluation.

~~~ and/or join me for a class! ~~~

In my yoga classes, we practice poses where we can explore different sections of our spine – wisely – and bring awareness to how the whole spine interacts with the neighboring support of the shoulders, the hips and everything in the whole body – including the fingers and toes, even our eyes.

All under the brilliant reinforcement of the breath.

Yoga for Our Vital Bones and Yoga for the Care of Your Spine are places to experience this connection with your body, mind, and spirit. We come to know ourselves better on many different levels to enhance our mobility, balance, and experiences in life while reducing pain and the conditions that contribute to our fracture risk.

We are moving slowly, learning to use our breath to support our movements. We are not externally weighted or moving abruptly so yoga can be a place to learn to better understand ourselves, our bodies, and our moving in this world. This is how we adapt to our capabilities and capacities and keep communication systems online throughout our whole body as we age.

We must remember that our body is wise. It is designed to move and yoga exercises us on many different dimensions. We connect the physical parameters of our body with the physiology of its components; we practice paying attention, understanding our behavior, and taking note of the state of our emotions when we are moving. Practicing all these aspects of yoga takes practice.

~~~

~~~

Notes:

(1) Smith EN, Boser A. Yoga, vertebral fractures, and osteoporosis: research and recommendations. Int J Yoga Therap. 2013;23(1):17-23. PMID: 24016820.

(2) Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984 Oct;65(10):593-6. PMID: 6487063.

~~~

~~~

No Comments